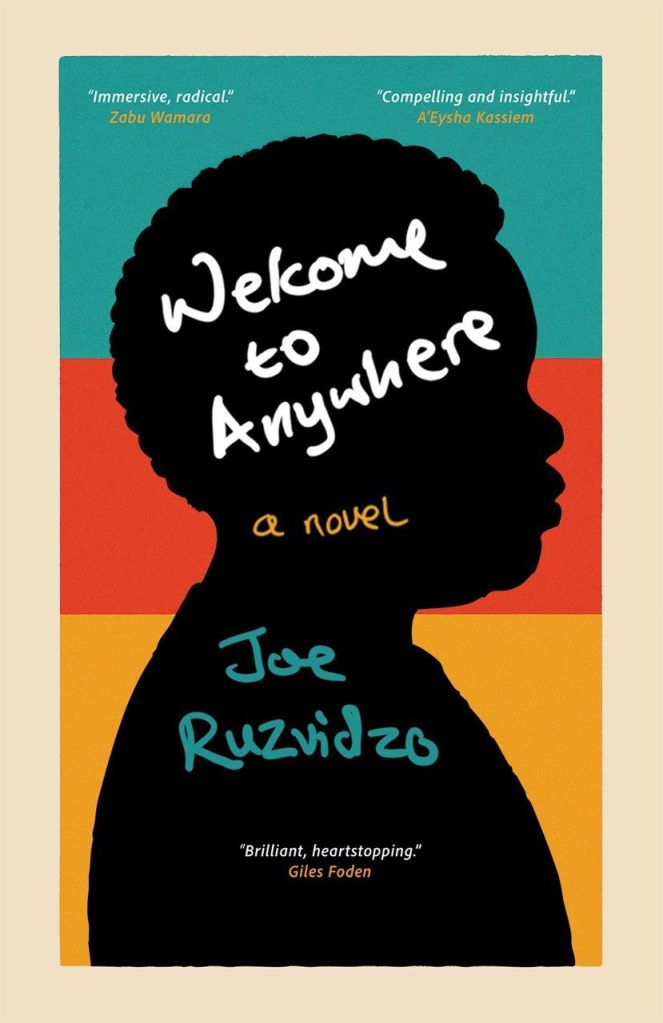

160 pp. September 3, 2025. Fiction/Zimbabwe.

It’s wonderful to encounter Billy again—Billy from “The Heist”, a short story in Joe Ruzvidzo’s 2017 Behind Enemy Lines and Other Stories . You won’t need to have read “The Heist” (I did read it again after I finished this novel), although Welcome to Anywhere is an expansion. It tells us more about Billy: lots more about how chubby he is and how ordinary (at the beginning of the story, anyway), and more about what happened to his father and some about his mother:

“During wartime in the town, Mai Billy’s daily routine as a teenage girl was a delicate dance between the shadows of conflict and the toughness that youth demanded. Living under her parent’s roof, she navigated a world of uncertainty and sacrifice, where each day carried the weight of hope and fear. … She carried the hopes of her family and community on her shoulders, a corpulent example of optimism in the face of adversity.”

So you know where Billy gets that from.

We get a lot more background about how Comrade (the most important character, apart from Billy) came to be in Chemadhegudhegu. And we learn Comrade’s thoughts about—or perhaps excuses for—how he ended up on the wrong side of the war, committing atrocities against his own people:

“Do you think I wanted it? The voice came again, gruff and full of old bitterness. You think I wanted to be the man I became? A man with blood on his hands, whose friends were nothing but names on graves, whose enemies … well, they disappeared into the earth, too. I didn’t ask for it, boy. But once you’re in, you’re in. It gets under your skin, the need to survive. It changes everything about you, down to the way you walk and the way you think. There’s no going back to who you were before.”

There’s a link between Comrade and Billy’s father which is explained in Welcome to Anywhere, a possible (hmmm) reason for what happens to Billy during the heist. And then, finally, we learn more about that ridiculous heist, and its effect on Billy.

We finally leave Billy when he’s turned sixteen.

This is the story of Zimbabwe’s liberation war and its enduring effects: Comrade’s shiftless existence as a disabled veteran, the effect of the loss of Billy’s father on his family, and how so-called ‘dissidents’ turned to crime. That last bit is in fact one of the weakest parts of the novel for me, even if it’s central to the story (it’s why the heist happens).

What I found really very powerful is the story of Billy’s possession (although I’m still not sure how that happened…). Through it Billy relives, in dreams and visions, the liberation struggle, or Chimurenga—mainly his father’s experiences, but also those of his ancestor, one of the heroes of the struggle (and a personal hero of mine), Chief Chinengundu Mashayamombe:

“The dream shifted, and wind howled through the thick canopy, carrying the scent of damp earth and crushed grass. The rifles, loaded and ready, felt steady in the hands of the warriors crouched in the shadows of the trees. Chief Mashayamombe, tall and unyielding, stood at the centre of his people, his eyes scanning the open valley before them.

The chief’s heart beat steadily, calmly. This wasn’t an attack for its own sake – this was justice. The settlers came with their rifles and their wagons, claiming what wasn’t theirs, enslaving those they couldn’t kill outright, driving his people from their homes. They built fences and burned the crops. They tore up the sacred groves where generations of ancestors had been laid to rest. And they did it with sneers on their faces, as though it were their divine right.

Today, the land would answer.”

I found this section of the novel very moving. This passage spoke to an ache I didn’t know I had: for depictions of our heroes—particularly in literature, but also in film. For stories about us, told by us, for us. The story of Zimbabwe has not fully been told yet to or by this generation. Billy (and Ruzvidzo, too) echoes my thoughts:

“He often wondered why no comics contained heroic tales of real-life legends like Chief Chinengundu Mashayamombe with his long dreadlocks, but until there were, he’d make do with what he could get in the Anywhere Pharmacy.”

Ruzvidzo says apologetically in the Acknowledgments that ‘the next one will be better’ and it’s true: it feels like Welcome to Anywhere was a bit of a struggle. The early parts of the novel (before the heist) feel largely overwritten—almost as if Ruzvidzo was standing outside of himself, watching himself write. This slowed my reading down significantly.

“The farms are meticulously maintained, and each field and furrow are a tribute to the discipline and diligence of the farm workers, if not the farmers themselves. The dawn here is announced by the meditative hum of morning chores as the workers make their way into the fields. The rising sun paints a dreamy silhouette against the brightening sky.

Beyond the farmlands lie the cotton fields. These vast white canvases bloom under the generous African sun, cotton balls peeking through the green leaves like tufts of cloud fallen to earth. Harvest season brings a flurry of activity as workers and machines descend upon these fields, with noise, laughter and banter echoing over the landscape.”

I don’t believe those parts of the novel are necessarily in Ruzvidzo’s own distinctive voice; that I felt came through a lot more in his earlier collection of short stories, Behind Enemy Lines and Other Stories.

And then, as I’ve said, I didn’t care very much for the bits depicting Zimbabwe’s alleged ‘dissidents’, although I very much appreciated Ruzvidzo trying to tell that complex story. This is Ruzvidzo’s version of the tale, not the one I wish had been written; it’s a beginning, and I’m sure there will be others.

So much for my thoughts about Ruzvidzo’s debut novel. I enjoyed meeting Billy again, the deepening and darkening of his story, and the hopeful note at the end for his future. He doesn’t quite come of age in this novel, but he certainly comes a long way from that fat and ordinary boy to whom nothing ever happens.

Many thanks to Joe for providing me a copy of Welcome to Anywhere for review.

Leave a reply to September 2025 reads – Harare Review of Books Cancel reply