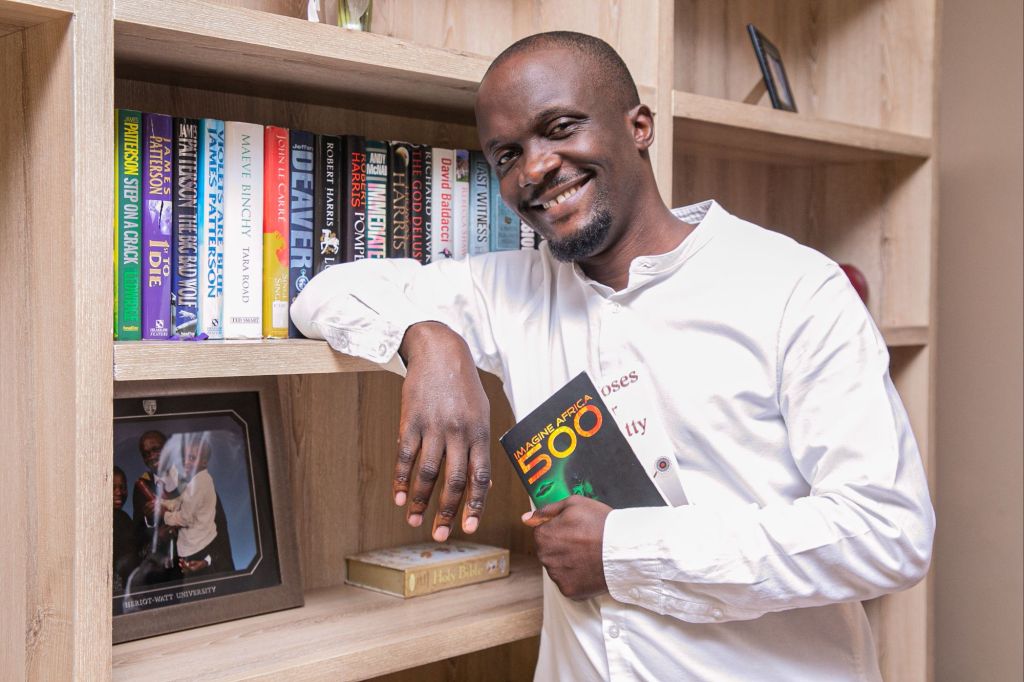

HRB is happy to bring you this fun and illuminating chat with Muthi Nhlema, the author of Piss Corpse.

Thank you to Muthi for his generous (and super quick!) responses to these questions, and to Ivor Hartmann for the connection.

About Muthi:

When he isn’t managing a non-profit or trying to understand his 12-year-old son’s obsession with anime, Muthi Nhlema is a Malawian writer best known for his adventures (and misadventures) in African speculative fiction.

His first novella, Ta O’Reva, which imagines Nelson Mandela’s return to a post-apocalyptic South Africa, won third prize in the 2015 International Freeditorial Long-Short Story Competition and was shortlisted for Best Novella at the 2017 Nommo Awards. An excerpt, Legacy, was longlisted for the 2015 Writivism Short Story Prize and was runner-up for the 2015 Dede Kamkondo Short Story Award. His short story One Wit’ This Place was the opening piece in the speculative fiction anthology Imagine Africa 500 and was named one of the top 10 African speculative short fiction stories of 2016 by renowned writer and editor Wole Talabi. His second novella, Hiraeth, from the speculative eco-fiction anthology Mombera Rising, made the longlist for the 2024 British Science Fiction Association Awards. In 2021, while battling writer’s block disguised as imposter syndrome, Muthi was selected for the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa, becoming the fifth Malawian to join since 1967.

Jacqueline for HRB: Piss Corpse is really funny, and I like Mbumba and Charlotte’s warm relationship. How did you think this story up?

Muthi Nhlema: Honestly, Piss Corpse was an accidental joy to write. A year before I started it, I wouldn’t have imagined wanting to write that story at all. Looking back, though, I can see how little moments, random observations, and personal experiences all quietly laid the groundwork for it. It’s one of those unexpected privileges in writing when a story emerges almost by surprise.

Part of what shaped it was my fascination with how non-Malawians—especially Westerners—find certain aspects of Malawi both fascinating and bewildering. For example, here it’s perfectly normal to show up at a wedding you weren’t invited to—there’s always a wedding somewhere on a Saturday, and being alive is invitation enough! To Malawians, that’s ordinary. To visitors, it can be strange or even shocking.

I’ve also noticed how my non-Malawian friends sometimes expect me to be offended by things that don’t offend me at all. It’s not that one reaction is better or worse—just that we’re shaped by very different contexts. Those moments, when “the woke encounters the unbothered,” are often unintentionally comic, at least to me. It’s that mismatch of expectations that I find so interesting.

But the specific spark that actually got me writing was hearing about a Canadian friend’s awkward experience in a Pentecostal church here. I found it hilarious—not in a mocking way, but because it captured that genuine discomfort of encountering new cultural territory, especially when you’re trying hard to be respectful or, as in Charlotte’s case, “woke” and it just makes you even more self-conscious. I wanted to capture that fumbling, human awkwardness of trying (and failing) to get it right in someone else’s cultural space.

So really, the story is a mix of all those little observations and one very vivid moment of culture clash. It was an accidental joy—and looking back, I’m glad it surprised me.

HRB: Mbumba is delightfully typical of many young African women—commonsensical, generally, but rather flightily religious. So: Is your story also a commentary on the rise of non-mainstream religion in Africa?

MN: That’s a very interesting question. To be honest, when I was writing Piss Corpse, I didn’t really have a conscious agenda, particularly about non-mainstream religion. Like with many stories, you often don’t fully understand in the moment what kind of story you’re telling or why it’s going in a certain direction. A lot of that only becomes clear in hindsight.

Now that it’s been published for a few months and I can look at it with some distance, I think if there is any underlying commentary, it’s about the performative nature of non-mainstream religion—specifically the charismatic variant of Christianity. Often, as Africans, we look at what’s happening in the West and think it doesn’t make sense, or we’re quick to dismiss it as purely performative or insincere. But we don’t always recognize that we can be just as performative ourselves.

Whether it’s cultural practices we don’t really believe in or understand but keep performing anyway, or the spectacle that can come with certain religious expressions, there’s an element of performance that’s universal. In hindsight, if the story is making any point, it’s that this performative impulse isn’t something uniquely Western—it’s something we share. We’re just as capable of performing for the crowd, for the spectacle, as anyone else.

HRB: Did you have any trouble writing the story from Charlotte’s perspective? What made you choose hers rather than Mbumba’s?

MN: Honestly, it wasn’t very difficult to write Charlotte as a character because she’s everywhere online. If you go on YouTube, TikTok, or Instagram, you’ll find countless versions of her. Charlotte is a well-meaning, liberal, agnostic Westerner who genuinely wants to do good and has a chip on her shoulder against the patriarchy. But that well-meaning impulse can come across as overly judgmental or self-righteous. She lives in a kind of bubble that shapes how she sees the world, convinced not only that she’s right, but that she’s righteous. That type of person is well-documented online—that it was quite easy to observe and imagine how she would think, speak, and behave.

As for why I chose Charlotte’s perspective over Mbumba’s—it was really about challenging myself. With Mbumba, even though there are aspects of her experience that I can’t fully know without investigation (for instance, her experience as a woman), many parts of her worldview felt familiar to me. Things like her ‘commonsensicalness’ , being casually or flightily religious, —those are things I understand intuitively.

But Charlotte’s perspective is fundamentally not my own. She’s white; I’m black. She’s a woman; I’m a man. She’s agnostic; I believe in God. I wanted to see if I could step into that very different viewpoint and tell a story from there, making it feel authentic and grounded. I wanted to capture what it’s like for someone like her to arrive in Malawi and see all its strange, beautiful contradictions for the first time. For me, that was the real challenge: could I write her perspective as convincingly as I would my own?

HRB: Although this story isn’t at all critical of the Peace Corps, the name implies it could be, and the whole idea of the Peace Corps has come in for some criticism among today’s younger, more woke Africans. You didn’t touch on this in this story. What is the reception of the Peace Corps in Malawi in general?

MN: There were definitely aspects of writing Piss Corpse that were accidental or just emerged in the moment. But one thing I was very intentional about was keeping it focused squarely on cultural satire. I really wanted to capture the awkwardness that happens when a very “woke” Westerner comes to a place where people are largely unbothered by the things that offend them, and then tries to navigate that landscape. That culture clash, to me, was just such fertile ground for humor—and I really wanted to write something funny.

If there’s any broader commentary in the story, it’s about expat culture in general. One thing that’s always struck me is the contradiction of expats coming to Malawi to “help the poor” while enjoying first-world privileges—fine dining, imported luxuries—and then going to work the next day to advise Malawians on poverty alleviation. I didn’t want to preach or lecture about that, but I did want to show it, because those contradictions are both jarring and revealing. That’s why I chose to frame the whole thing as cultural satire, to let readers see those hypocrisies for themselves.

As for what Malawians think of the actual Piss Corpse – sorry! – Peace Corps? Overall, I’d say the perception is generally very positive. Peace Corps has been here for a long time, and volunteers often work in rural areas teaching English or helping with other development-focused projects. They tend to be seen as friendly, approachable, and willing to live simply alongside local communities.

But there’s also a kind of mild puzzlement or even quiet suspicion in some quarters about their intentions. For some Malawians, it’s strange to see someone voluntarily living with limited comforts—there’s this sense of “Why would you choose this if you don’t have to?” And even if the intent is good, it can come across as superficial or performative, because everyone knows the volunteer is eventually going back to a far more comfortable life. It’s a mild hypocrisy Malawians often just brush aside.

HRB: Do you think of writing as a political tool at all?

MN: What is politics, if not the shaping of people’s minds? In that regard, I do think writing has the power to be political. I’ve always believed that writing is its own special kind of magic. Think about it: someone might have written something 200 or 300 years ago—someone I’ll never meet, someone who exists for me only in history books—and yet their words still carry power today. They can still inspire, motivate, even spark an uprising.

That’s remarkable to me—that something you once held in your head, you put into words, and then that same idea can be planted in someone else’s mind generations later. That’s a very special kind of magic, and it’s part of why writing can be such a potent political tool.

But I also want to emphasize that writing can be whatever you want it to be. It all depends on intent. It can be political, but it can just as easily be personal, entertaining, healing, or simply beautiful for its own sake.

HRB: How did you get into writing?

MN: My love for storytelling actually started when I was ten years old. I watched a movie called Hopscotch, starring the late, great Walter Matthau, who played a CIA agent who gets unceremoniously fired. In retaliation, he starts writing a tell-all memoir, revealing top-secret details with every chapter he publishes and shares with the world of espionage. The CIA, the KGB, Mossad—suddenly everyone wanted him dead. I was obsessed. I must have watched it twice a day at some point. And I remember thinking: How is it possible that words—just words—could cause so much trouble?

And because I was probably a little troublemaker at the time, the idea of writing as a form of mischief appealed to me. Even now, I still write with that little boy in mind—the one who couldn’t believe that a sentence could cause chaos.

HRB: I first encountered your work in Imagine Africa 500. I’m always keen to read more from “the warm heart of Africa,” but it’s relatively difficult to access the work of Malawian writers. Why is this?

MN: Your observation is correct—it is very difficult to get access to Malawian stories, especially well-crafted ones. I think there are many reasons for this, and other writers will have their own valid explanations. They might point to the lack of publishing opportunities, the absence of creative writing training for emerging writers, or the generally competitive and under-resourced literary landscape. All of these absolutely play a role.

But from my own observation, I think there’s something even more pervasive at work—a kind of literary feedback loop in Malawi. Here’s how it works. Within Malawi, it’s actually relatively easy to access creative writing, because the primary platform for publishing short stories is the local newspaper. A writer will craft a short piece, usually 700 to 1,000 words, and submit it in hopes it gets selected. Once accepted, the editing process is almost entirely focused on grammar, typos, and word count—not on content, structure, or overall quality.

As a result, stories that may be weak in terms of craft, character development, or originality get published without meaningful editorial feedback. This, in turn, sends a signal to other writers: “this is the standard that gets you published.” And so they write to match that bar. Over time, this reinforces itself. Writers begin to believe their work is good simply because it’s appearing in print, even though it hasn’t gone through rigorous, critical editing.

The real shock often comes when these writers try to submit to regional or international literary magazines—like Omenana or other anthologies—and receive tough feedback pointing out that their writing isn’t yet up to standard. It’s only at that point that many realize they need to break out of that local feedback loop. They start reading more widely, learning from other writers, and working to elevate their craft so they can tell Malawian stories in ways that resonate outside of Malawi as well.

So yes, in addition to all the other challenges—limited publishing opportunities, poor editing capacity, a small readership—this literary feedback loop is, in my view, one of the most deeply entrenched obstacles. It doesn’t just make Malawian stories hard to access; it makes well-written Malawian stories even rarer.

HRB: I’m intrigued by the genre of Piss Corpse, as I think of you more as a sci-fi/SF author (perhaps because of that first encounter). Do you have a preferred genre, or have your published works pigeonholed you?

MN: I think what’s happened is that I’ve been somewhat pigeonholed by my published work—most people know me as an African speculative fiction writer. And I accept that without any qualms or resentment. But for me, the approach has always been to find a genre that fits the story, rather than forcing the story to fit the genre.

When I write speculative fiction, it’s because there’s something in the story that requires that mode for it to work. For example, if the premise is the return of Nelson Mandela to a post-apocalyptic South Africa—that’s immediately speculative by nature. Or imagining Africa 500 years from now in Imagine Africa 500. Or even last year’s story imagining the Ngoni tribe in 100 years. These concepts demand speculation to be told effectively.

So I let the story determine the genre. If a story needs to be speculative, that’s what it becomes. If it doesn’t, it won’t be. That’s why Piss Corpse isn’t speculative at all. It’s very clearly a cultural satire set in the present day, with a realistic protagonist and no antagonist. The story itself was grounded in contemporary social dynamics, so I let it stay there. For me, it’s always about serving the story first.

HRB: I know there’s an active writing community in Malawi—the Malawi Writers’ Union is an excellent sign. Is there an active SF “scene” there as well?

MN: At the moment, I’d say there’s a bubbling writing scene in Malawi, particularly with the new leadership of the Malawi Writers’ Union, which is now headed by a speculative fiction writer, Shadreck Chikoti. That’s really encouraging. While there isn’t yet a true speculative fiction “scene” in the sense of a large, dedicated readership or many regular publications, the Malawi Writers’ Union is actively encouraging young writers to explore new areas of writing beyond the purely realistic or moralistic. For example, they recently closed submissions for a short story competition focused on the impact or influence of artificial intelligence—an effort to get writers thinking in more modernistic and even speculative directions.

Those of us who do write speculative fiction in Malawi tend to know and interact with each other quite often, so there is a kind of informal network. Interestingly, there’s growing interest from academia more than from the general public at this stage. For example, I and a few other writers have been invited to speak at the University of Malawi about speculative fiction. So there’s a recognition, especially in academic circles, of its importance and relevance as an emerging part of Malawian literature.

For now, I’d say there’s definitely momentum and promise—a bubbling writing culture that I hope will, in time, lead to a truly thriving speculative fiction scene in Malawi.

HRB: In there government support or promotion for the arts, and literature in particular, at all in Malawi?

MN: Well, I’d say when it comes to literature specifically in Malawi, there’s very little—if any—support from the government for its promotion. Even though the law provides for structures like the National Arts and Heritage Council, which is meant to offer grants to cultural organizations such as the Malawi Writers’ Union, in practice there has been very limited government backing to promote literature either within Malawi or abroad.

On an individual level, there are a few writers who’ve managed to have their work included in the school curriculum and who can earn some income that way, but those cases are rare. So overall, at the sector level, there’s been very little sustained or meaningful government support for the growth of literature in Malawi.

This is why, for the most part, the Malawi Writers’ Union survives on member subscriptions and donations from its own members. I know writers who have personally contributed money to fund short story competitions or to support the Union’s basic operations, because we all recognize that support simply isn’t going to come from the government. That’s the reality for creative writers in Malawi: we have to fend for ourselves to keep the craft alive and ensure it doesn’t die out.

HRB: You have two careers—one where you manage a non-profit, and this one, as a successful writer (you attended the International Writing Program at Iowa in 2021). Do you find it hard to balance the two, or do they feed into each other in some way?

MN: Actually, I keep both worlds very separate. My professional work is very technical in nature—I deal with a lot of data and numbers day to day—while my writing is a completely different headspace. In that sense, you could say I’m a very typical man: I’m one-track minded and I focus on the one thing I’m doing at the time.

If there’s any mingling between the two, it’s probably in the way my engineering background shapes how I approach sentences. As a civil engineer by training, I’m used to the idea that there can only be one correct answer—and it has to be precise. That mindset shows up in my writing because I get very particular about how a sentence is constructed. I want it to be just right. As a result, it really slows me down as a writer, because I’m constantly asking myself: is this the right word? Is this capturing what I mean exactly?

But apart from that, I try to compartmentalize the two worlds as much as possible—like most men on this planet do.

HRB: Who’s your current favourite writer, and why?

MN: This is always a tricky question for most writers because there’s this temptation to try to sound sophisticated. You’ll often hear people say Achebe, Dostoevsky, or Steinbeck—names that signal a certain literary gravitas. But if I’m being completely honest, I wouldn’t say Stephen King is my absolute favorite writer in some grand, abstract sense, but I do have more of his books on my shelf than anyone else. He’s the writer who really got me into reading seriously.

What really hooked me was one book in particular: The Stand, specifically the uncut version published later than the original 1978 edition. It’s well over a thousand pages long, and I remember being astonished that a book that big never felt boring. You’d expect there to be lulls or slow sections, but there weren’t any for me. I tore through it. That experience made me think for the first time: I want to write like this—to create a story that grabs you at the start and just doesn’t let up.

So if I had to pick one author, it would be Stephen King—not because it sounds impressive, but because he’s the one who showed me the sheer power of storytelling that can hold a reader for a thousand pages straight.

HRB: Are there other Malawian writers, past and present, you would recommend to people keen to explore Malawian lit?

MN: If you’re interested in writers from years past, I’d recommend Steve Chimombo, Dede Kamkondo, and DD Phiri. I’d also add Jack Mapanje to that list—he’s best known for his poetry, which is still quite significant in Malawi’s literary history and really worth reading to understand the national history.

As for more modern or contemporary writers, I’d mention Stanley Kenani, who’s the only Malawian writer to have been shortlisted twice for the Caine Prize. There’s also Shadreck Chikoti, who’s a real trailblazer for speculative fiction here, really picking up the mantle from earlier writers like Dede Kamkondo and pushing the genre forward. Wesley Macheso is another important figure—he’s an academic who, crucially, puts his pen where his mouth is. He doesn’t just critique Malawian literature; he actively contributes to it with his own writing.

I’d also highlight a couple of female writers who are making important strides. Ekari Mbvundula Chirombo has been doing impressive work in Malawian fiction, and Yanjanani Banda is another writer I’ve recently discovered who’s making inroads not just in Malawi but also on the wider African literary scene. These are all voices I’d recommend looking out for if you want to get a sense of the range and richness of Malawian writing.

HRB: Do you have any time to read? What’s on your bedside table right now?

MN: As a writer, I live by a very simple principle: if I’m not writing, I must be reading. If I’m not reading, then I must be writing. Since I’m not writing at the moment, I’m reading Yellowface by R.F. Kuang. I started it about two weeks ago, and yes—it actually sits by my bedside every night. I was tempted to ask you how you knew it was by my bedside, but I guess that’s something a lot of people do! So maybe I’m not that original after all. Damn it!

Links:

Leave a comment