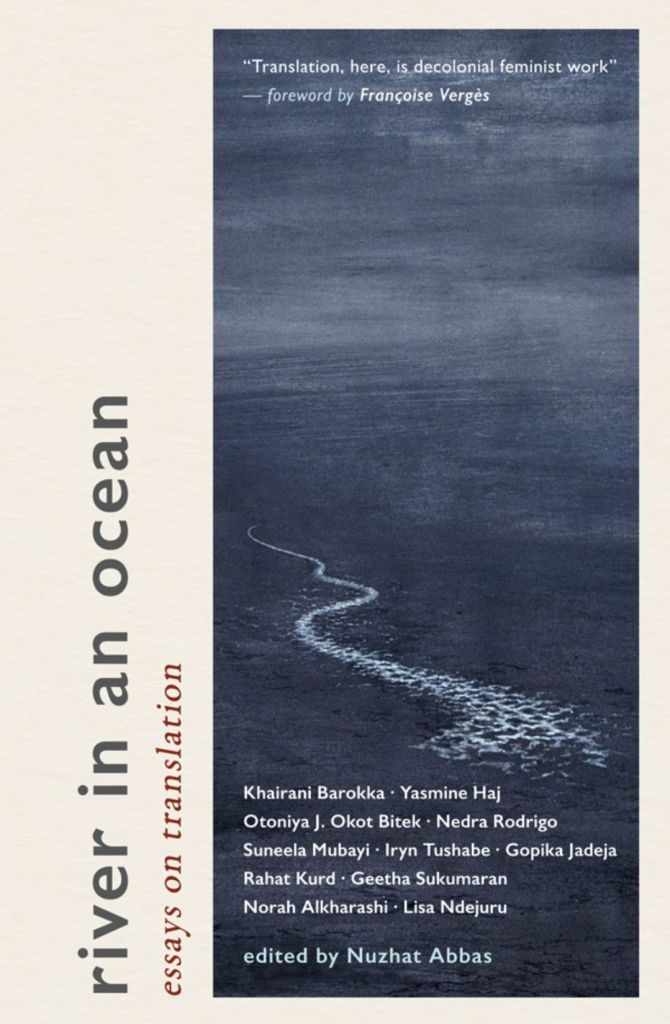

223 pp. Published June 1, 2023 by trace press. Non-fiction/essays.

I took my time over this collection of essays, and recommend that you do too. These writers present readers with much to consider when thinking about translation—from personal stories of getting into the work, thoughts on how to cope with racism and the separation of languages into classes, translating difficult works (like war stories), and so much more.

In the foreword, Françoise Vergès explains how trace press’s focus on decolonial translation aligns with her own feminist decolonial work and practice. She points out the great need for this in a world where the Far Right is seemingly gaining ground against the Global Majority, and where the Left is being overrun by neoliberal capitalism. She talks about how, even for her, with a French mother, “French … was the language of (post)colonial rule and power” while “Creole was the language forged in resistance, and our language of intimacy, but it was forbidden at school and in the media, and presented as a mere dialect.” This is the case for most of the essayists in this collection: a conflicted relationship with the language of the metropole which is, paradoxically, the reason for their work.

Khairani Barokka’s dual-language (Bahasa Indonesian-English) essay is the most trenchant on this, and on the deeply damaging emotional labour of translators who are not white in a market where their work is not often adequately recognised or acknowledged. These translators are frequently treated as simple intermediaries between their own culture and the white/Western translator whose name ends up on the final document or book cover. That this essay is written in two languages is breathtakingly poetic: it makes its point on the page before the reader even engages with the text, providing a visual rhythm with the juxtaposition of the two languages.

Yasmine Haj writes in her essay about the differing weights of languages, how Hebrew for her is authoritative, French neutral and semi-intellectual, and English “innocent”—a false innocence in a world where we’ve all been forcibly shaped by this language of Empire. And for Haj, Arabic is the language of everything else, of life, and loss, and play. Every language she has in her head is fraught.

Otoniya J. Okot Bitek’s contribution is a series of letters to her father, Okot P’Bitek, who wrote Song of Lawino and Song of Ocol—Lawino, the traditionalist, and Ocol, the “modern” urban African. She retraces her father’s footsteps in the UK as she considers her collaboration and engagement with his work, while thinking about decoloniality, national identity, and orality.

Nedra Rodrigo’s essay is a thoughtful discussion of how land and language are linked—tinai (“landscape”), while translating Tamil. Suneela Mubayi’s The Temple Whore of Language is a beautiful consideration of “mixed gender and mixed languages”; of how their identity sensitises them to nuance instead of the rigidity of boxes—helpful when translating from and into various languages; and of translation as unsettlement. Iryn Tushabe’s Saved muses on Christianity, coloniality, the Ugandan school system and the English language. Gopika Jadeja thinks about caste and language in translating Dalit poetry. Rahat Kurd’s Elegiac Moods is also epistolary, in letters to Agha Shahid Ali, the Indian-American, Kashmiri Muslim poet. Lisa Ndejuru made me think about what we lose when we translate African oral tradition and history, often in the form of songs, to paper. She examines Rwandan history as mediated through recordings—translated and transcribed—of ibitekerezo by a colonial Belgian historian, Jan Vansina, in the 1960s just before independence.

The individual pieces in River in an Ocean form a much greater whole, a picture of what it means to be a Global Majority translator. There are common themes: colonial damage, language loss, a certain level of disregard and even contempt from those in the position of dominance (language and cultural dominance being interchangeable), and also a deep yearning—a stance as advocates, even—in those working in translation for the preservation of (minority) languages and culture. Across the collection, each translator’s attention to and love for language are clear.

River in an Ocean advances a position that’s even more compelling now in our globalised world, that translation is crucial for increasing connection and understanding, but also that it’s important to preserve the diversity that causes us to need translation in the first place. It requires some delicacy, perhaps, to successfully thread the needle; but there are many thinkers considering what the future of translation could or should be, and the writers of these essays are some of them.

Thank you to Nuzhat Abbas and trace press for a DRC.

Affiliate link: Support independent bookshops and my writing by ordering it from Bookshop here.

Leave a reply to #WITMonth 2025 – Harare Review of Books Cancel reply