320 pp. Published January 7, 2025 by NYU Press. Non-fiction.

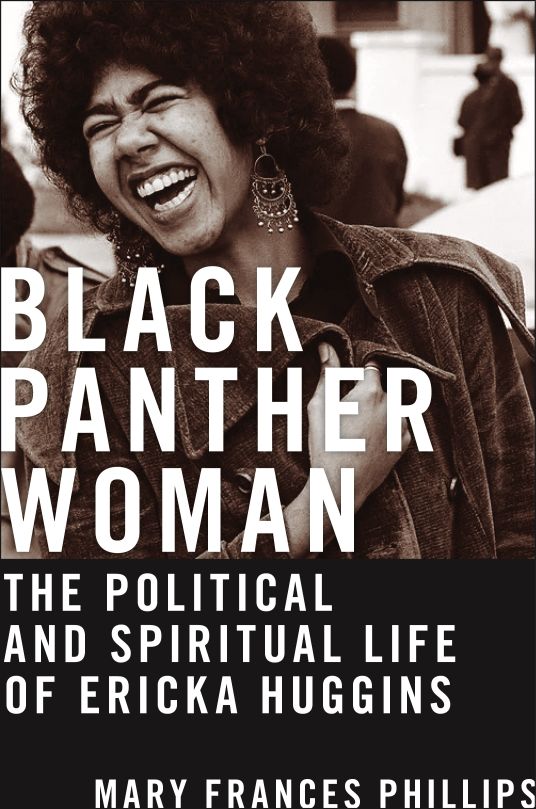

Due to my enduring interest in the 1960s, the Black Panthers loom large in my imagination: men in black berets, women in Afros, the Black Power salute. I’ve pored over photographs of them and the artwork they produced ([Black Panther: The Revolutionary Art of Emory Douglas – Emory Douglas]), and regularly go back to archives of their newspapers. I even know some of the great figures in the BPP who happened to be women: Kathleen Cleaver, Elaine Brown, Afeni Shakur… And yes, Ericka Huggins. But I don’t know enough; so I welcomed this essential intervention into the history of one these heroes of the BPP and the Civil Rights Movement.

What’s special about this biography is that Mary Frances Phillips had access to Huggins through a series of interviews, in addition to archival sources and personal material that Huggins made available. This led to a quite personal and intimate biography, centring the thoughts, feelings and memories of Huggins herself—from the time she was imprisoned, a new mother, just after her husband had been killed by he police, through her years in the BPP, and after. Readers get insight into that time in prison as a Black woman at the height of COINTELPRO and the action against the BPP and other civil rights organisations, and then later as the BPP closed ranks against these external forces. Huggins’s voice is an important record in light of the BPP’s sexism and other forms of violence within, which has been extensively discussed elsewhere: Huggins was right there in the midst of it.

The goal of this biography is to highlight Huggins’s spiritual wellness practices as the way she coped with her struggles and trauma, and also how they’ve shaped her legacy; Phillips makes this point well. My main criticism, however, is the tendency to repetition; Phillips makes the same points over and over again as she tries to pull the threads of Huggins’s experiences into a cohesive narrative that fits this goal. Still, Black Panther Woman is timely, a potential manual for life for activists when it feels again like civil rights are at such great risk. As a historical record, there are fascinating details, as mentioned, about what life was like for Huggins—a young woman and mother deeply embedded in the BPP—and highlights of many of the activities that the BPP is now well known for. Mainly, this is giving Huggins her flowers while she’s still alive, and a sensitive and personal tribute.

Thanks to NYU Press and Edelweiss for early access.

Affiliate link: Support independent bookshops and my writing by ordering it from Bookshop here.

Leave a reply to My late intervention for #IWD2025 – Harare Review of Books Cancel reply