I’ve been catching up on short classics as 2021 comes to an end, mostly because I’ve had absolutely no concentration left for any proper reading (as you would expect: it’s holiday season!). (My currently reading list is out of control, and showing no sign of being completed.)

So, here are four:

Season of Migration to the North x Tayeb Salih. Translated by Denys Johnson-Davies.

First published in 1966.

Finished reading on Dec 15, 2021.

Genre: Fiction.

Supplied blurb: After years of study in Europe, the young narrator of Season of Migration to the North returns to his village along the Nile in the Sudan. It is the 1960s, and he is eager to make a contribution to the new postcolonial life of his country. Back home, he discovers a stranger among the familiar faces of childhood—the enigmatic Mustafa Sa’eed. Mustafa takes the young man into his confidence, telling him the story of his own years in London, of his brilliant career as an economist, and of the series of fraught and deadly relationships with European women that led to a terrible public reckoning and his return to his native land.

But what is the meaning of Mustafa’s shocking confession? Mustafa disappears without explanation, leaving the young man—whom he has asked to look after his wife—in an unsettled and violent no-man’s-land between Europe and Africa, tradition and innovation, holiness and defilement, and man and woman, from which no one will escape unaltered or unharmed.

Season of Migration to the North is a rich and sensual work of deep honesty and incandescent lyricism. In 2001 it was selected by a panel of Arab writers and critics as the most important Arab novel of the twentieth century.

An important post-colonial read, this had been on my TBR for a very long time. I didn’t expect what I found, though, when I finally read it: a beautiful, poetic, and lyrical book, full of truth and wisdom. Also some amusing asides as the story built up to its tense central story, and rather horrifying conclusion.

The blood of the setting sun suddenly spilled out on the western horizon like that of millions of people who have died in some violent war that has broken out between Earth and Heaven. Suddenly the war ended in defeat and a complete and all-embracing darkness descended and pervaded all four corners of the globe …

The darkness was thick, deep and basic — not a condition in which light was merely absent; the darkness was now constant, as though light had never existed and the stars in the sky were nothing but rents in an old and tattered garment.

Has not the country become independent? Have we not become free men in our own country? Be sure, though, that they will direct our affairs from afar. This is because they have left behind them people who think as they do.

(The truth about post-coloniality, in a nutshell.)

By the standards of the European industrial world we are poor peasants, but when I embrace my grandfather I experience a sense of richness as though I am a note in the heartbeats of the very universe.

(This broke my heart)

I loved this book, and I was transported to and immersed in Sudan for the duration. This is also the first book I’d recommend to anyone trying to understand the damage colonialism has wrought and continues to wreak on the minds on the formerly colonised. It’s also just a wonderful story.

Rated: 10/10.

A Small Place x Jamaica Kincaid

First published in 1988.

Finished reading on Nov 17, 2021.

Genre: Essay.

Supplied blurb: Lyrical, sardonic, and forthright, A Small Place magnifies our vision of one small place with Swiftian wit and precision. Jamaica Kincaid’s expansive essay candidly appraises the ten-by-twelve-mile island in the British West Indies where she grew up, and makes palpable the impact of European colonization and tourism. The book is a missive to the traveler, whether American or European, who wants to escape the banality and corruption of some large place. Kincaid, eloquent and resolute, reminds us that the Antiguan people, formerly British subjects, are unable to escape the same drawbacks of their own tiny realm—that behind the benevolent Caribbean scenery are human lives, always complex and often fraught with injustice.

A very quick read, and my first Kincaid.

This was so clever, so charming. I found myself laughing a lot, and also feeling quite a bit of despair at the post-colonial commonalities between what Kincaid described, and my own miserable country. Sigh.

Since we were ruled by the English, we also had their laws. There was a law against using abusive language. Can you imagine such a law among people for whom making a spectacle of yourself through speech is everything?

But people just a little older than I am can recite the name of and the day the first black person was hired as a cashier at this very same Barclays Bank in Antigua. Do you ever wonder why some people blow things up? I can imagine that if my life had taken a certain turn, there would be the Barclays Bank, and there I would be, both of us in ashes.

(🤣)

Still, all the very sharp criticism of colonial types more than made up for the sadness; I thoroughly enjoyed that.

Rated: 8/10.

Wide Sargasso Sea x Jean Rhys

First published in 1966.

Finished reading on Dec 21, 2021.

Genre: Fiction.

Supplied blurb: Wide Sargasso Sea, a masterpiece of modern fiction, was Jean Rhys’s return to the literary center stage. She had a startling early career and was known for her extraordinary prose and haunting women characters. With Wide Sargasso Sea, her last and best-selling novel, she ingeniously brings into light one of fiction’s most fascinating characters: the madwoman in the attic from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. This mesmerizing work introduces us to Antoinette Cosway, a sensual and protected young woman who is sold into marriage to the prideful Mr. Rochester. Rhys portrays Cosway amidst a society so driven by hatred, so skewed in its sexual relations, that it can literally drive a woman out of her mind.

Ugh. I can’t say I liked this book, at all. I disliked the narrator. I hated the way her mother treated her. I felt some sympathy for the mother, and wanted to hear her story, instead. I hated how bleak the setting was, atmospherically oppressive even while being beautiful. I liked the mysterious black figures in the book, but hated Antoinette’s descent into m̶a̶d̶n̶e̶s̶s̶ mental illness (was she, though? Mentally ill?)

I don’t know. I’m hard to please, and this didn’t please me. Maybe I needed to first read it when I was younger. Maybe I need to have a suitably analytical background (in literary terms). I just didn’t like it.

Rated: 4/10.

We x Yevgeny Zamyatin. Translated by Gregory Zilboorg.

First published in 1924.

Finished reading on Dec 26, 2021.

Genre: (Dystopian) Fiction.

Blurb: We is a dystopian novel by Russian writer Yevgeny Zamyatin, written 1920-1921.

The novel was first published as an English translation by Gregory Zilboorg in 1924 by E. P. Dutton in New York. The novel describes a world of harmony and conformity within a united totalitarian state.

It is believed that the novel had a huge influence on the works of Orwell and Huxley, as well as on the emergence of the genre of dystopia. George Orwell claimed that Aldous Huxley’s 1931 Brave New World must be partly derived from We, but Huxley denied it.

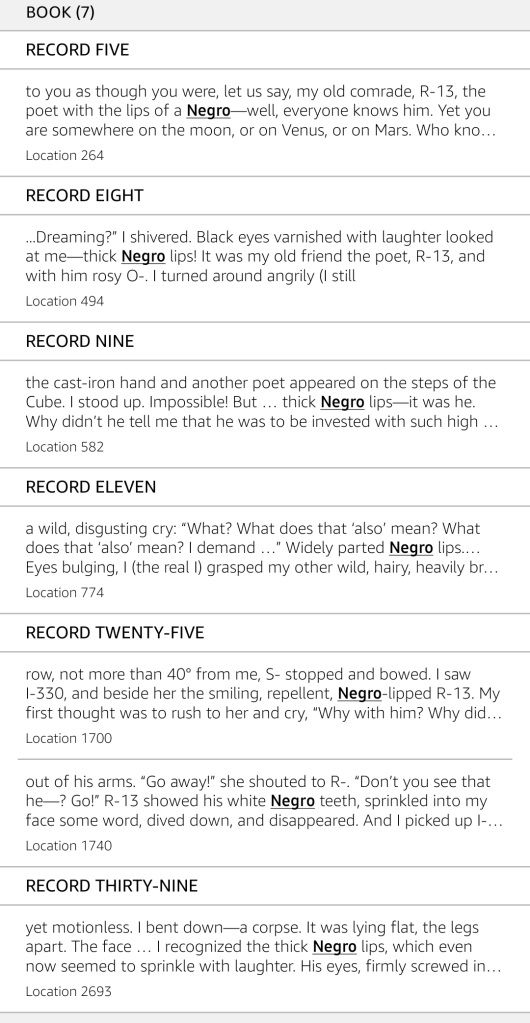

I struggled quite a bit with the style (of the translator, perhaps, and I’ll try a later translation sometime). I was, however, very impressed with how modern this story from 100 years ago is, given how much I dislike classic SF for how dated it becomes. Which is not to say I didn’t cringe mightily every time D-503 mentioned R-13 (his poet friend)’s thick Negro lips:

… Being, as I suppose I am, Negro, and with, as I have, thick lips.

Regardless. I can see that this was indeed the first of this kind of fiction—the granddaddy of dystopian fiction—and that it’s impressive for being that. Would be interesting to watch the movie, because I can picture it all: basically, the North Korea of our imagination + glass everywhere and free, uninspired sex.

Rated: 6/10.

Leave a reply to December 2021 reads – shona reads Cancel reply