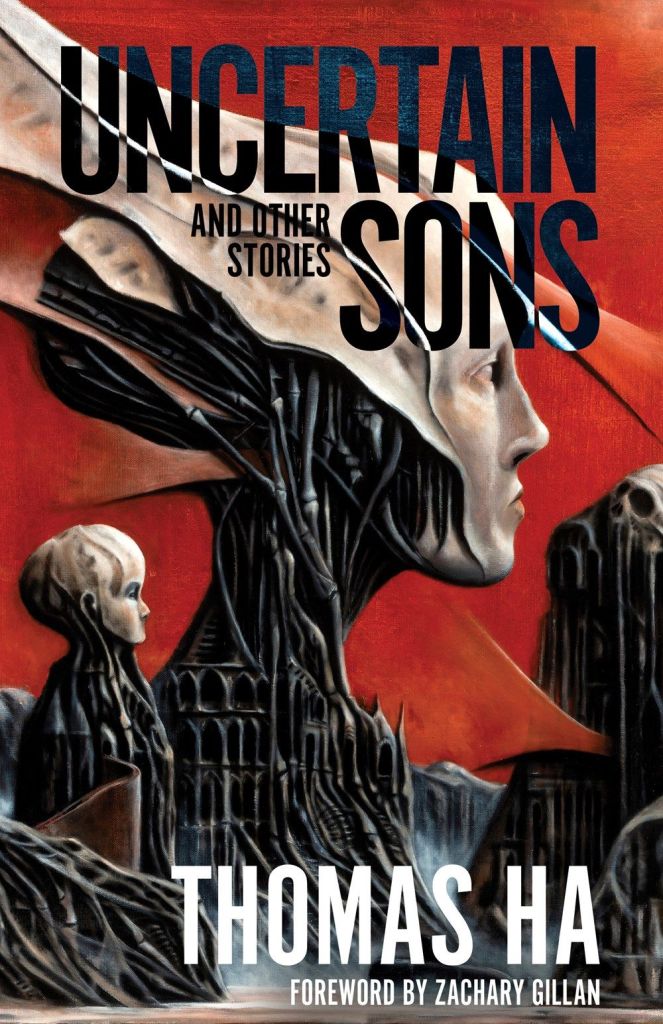

284 pp. September 16, 2025, Undertow Publications. SFF.

This collection starts with a seemingly innocuous story: The tenth time Jakey breaks the rules, he puts a sandwich in the mailbox for the “window boy.” This window boy is his friend who comes during the night just to chat—at first. As the story unfolds, it becomes clear Jakey’s world is not quite like ours; something terrible has happened to make the rules necessary, and Jakey’s behaviour is putting his family at risk. It’s wonderful how Ha inhabits the POV of this young boy as he reasons through for himself what the adults have told him, and whether he agrees that the world is as dangerous as they think. It’s a story that’s quite typical of this collection, and of Ha’s considered style.

There are all kinds of monsters here—monsters with tendrils and tentacles, but also some that appear human. And others somewhere in-between:

“In the shadows I see an anchor shamble, its silhouette like an armless man, as it pushes against the side of the house, rubbing its moist forehead on the walls.”

Ha’s characters stand up to them—most memorably in the Western-style novelette that closes out the collection, and for which it’s named. A character says, speaking for a monster and mocking the protagonist: “Uncertain fathers make for uncertain sons. And those boys grow up and become uncertain fathers, with their own uncertain sons.” But this protagonist, like so many others in the collection, is unfazed. Nor is Mary, in Where The Old Neighbors Go: With everyone minding their own business, no one ever asks what happened to the couple that lived across the road—but Mary does, and unmasks and confronts a creature that seems “like an ordinary gentrifier at first glance” (the ultimate suburban horror story).

In the uncomfortably-named Cretins, a form of sleeping sickness makes people fall asleep uncontrollably—even in public places, with all of the chaos that entails. To one man’s horror, he discovers he has a stalker. And The Mub is a wryly amusing and rather horrifying story with a different kind of stalker: a monster that sounds (cleverly) like AI and obsessively wants to show you what it can ‘create’—but it really just wants to feed on your thoughts like a leech: ”Just don’t…you know, do anything stupid, or give them new thoughts to ponder and try. And don’t ever let their thinking go the other way, through you.”

There’s an echo of this argument that artificial intelligence is not real in any true sense in Alabama Circus Punk, where a repairman who comes to fix a smart house turns out to be violently hostile to the robot ‘family’ within. As with the characters in The Mub, he doesn’t think AI understands meaning—in this case, bereavement. Ha leaves it up to the reader to decide the truth.

He again considers meaning, this time through the preservation of memory and the past, in The Brotherhood of Montague St Video. The protagonist, a freelance “re-writer”—apparently necessary in a world of manufactured progress, forward movement and efficiency, where people want neither the past nor what they consider unnecessary complexity—sifts through his mother’s possessions to work out what’s worth keeping. A character in this story ponders the importance of mental landmarks in producing existential meaning: “That’s the benefit of the work we do in preserving things in particular forms… We remember who we were then, so that we know who we are now.”

Balloon Season muses on family dynamics in the midst of apocalypse: In a world where semi-sentient and malevolent jellyfish-like balloons drift over the land every summer, would you be the brother focussed on protecting your children, or the one fighting to protect the wider community? Who’s the bigger hero? In Sweetbaby though, the dynamic is chilling: The parental figures have chosen the welfare of their monstrous child over that of the protagonist, to the point of allowing her to be killed multiple times.

Ha’s collection is a triumph of storytelling. In some ways, it’s not even important to find a throughline that holds these tales together, as each stands very well on its own. If there’s a theme, perhaps it’s that Ha’s characters are recognisably and understandably human in worlds that have veered towards the bizarre and apocalyptic—sometimes more science fictional, and other times fantastical.

But why read this kind of fiction at all? Zachary Gillan, who wrote the foreword to this collection, says in an essay at the Ancillary Review that this kind of fiction is “the first step towards envisioning a better world”—”by recognising what’s wrong with this one.” And as Barlow Adams says on Bluesky

“I feel as if the brutal realism of the current landscape basically demands weird fiction. This stuff is too much to process it directly on a day-to-day basis. It must be filtered through the weirdest lens until it resembles something like life, like hope or sanity.”

But Ha’s stories are also fun, and exceptionally well-written. If you read them for no other reason, read them for that.

Highly recommended. Thank you to Undertow for an early review copy.

Affiliate link: Support independent bookshops and my writing by ordering it from Bookshop here.

Leave a comment