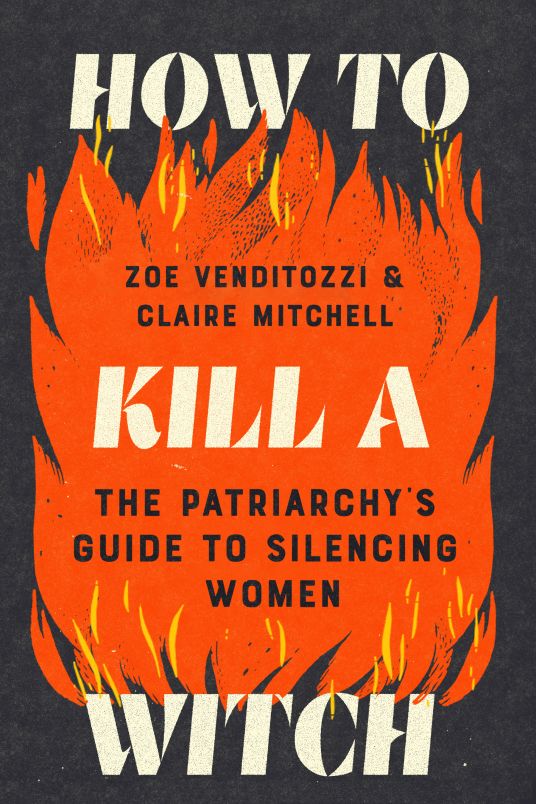

320 pp. September 30, 2025, Sourcebooks. Non-fiction.

Women (mostly women) are witches and have been for millennia in all kinds of different cultures; that’s kind of the basis of the whole patriarchy thing, or (cause, effect?) maybe the patriarchy led to women being called witches when they were just living their lives and yes, being quarrelsome and/or making healing potions.

Thing is, though, the Yarchy didn’t stop at name-calling: no, people were subsequently murdered, in public and really brutally, on really flimsy pretexts. It happened a lot in Scotland (not exclusively, but a lot, and there’s documentation), and that’s what this book is about.

The most surprising thing I learnt in this book? Perhaps not the point the authors were trying to make, but I was really surprised at how many men were accused along with the hundreds of women. I kind of want to know their stories too: Were they just caught up? Was it by association? Was it the same thing as many of the women—that is, just an accuser settling a score?

Anyway, this book makes for very grim but so very compelling reading. Turns out that not that many were burnt to death at the stake, as popular imagination has it; very frequently, these poor people were strangled to death and then burned—so they wouldn’t come back as revenants. Which brings us to the famous story of Lilias Adie, who was buried on a beach under a very large rock and still made it out, albeit in the saddest way. Amazingly, we even have an idea of what she looked like: a forensic artist, Dr Christopher Rynn, created a reconstruction of her face in 2017.

All very fascinating; and additionally so to me because those colonisers brought their Witchcraft Acts to Africa—as a tool of control, of course—and the results are still echoing today: two men were convicted and recently sentenced in Zambia for ‘attempting to bewitch’ the president, Hakainde Hichilema. It’s not at all that ‘witchcraft’ is unknown here (it’s far more complex than coloniser imagination, for sure), but witchcraft laws are still on the books in many countries (not Zimbabwe anymore—I’m going to ask a lawyer to ELI5) and are, naturally, frequently abused by the state. Not to mention accusations from jealous neighbours and as part of family feuds and things. So.

One more thing: Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne, and of course Tituba. The authors present the Salem Witch Trials of 1692 as a case study, probing why those much smaller trials are far more famous and led to a public reckoning and repentance, as well as a memorial. As the authors say:

“[The] truth is that the trials in Europe, particularly in Scotland, were larger, more widespread, and bloodier, with much higher death tolls.”

This book is part of a campaign by Venditozzi and Mitchell to make visible the victims of these terrible acts in Scotland and to seek an official apology. They say:

“The campaign has sparked a worldwide cultural conversation about women’s history and women’s place in the modern world. Today, the campaign works toward its remaining aims of creating a national memorial and a legislative pardon and is actively working with a number of Witches of Scotland–inspired groups throughout the country to bring these aims to fruition.”

It’s also a dire warning about what public panics can lead to. Times haven’t changed as much as we imagine, as the final section of the book (and the case in Zambia, above) shows. It’s probably why we hear the term “witch hunt” so much in the news still. Times only appear to change; humans, not even so much.

Thank you to Sourcebooks and NetGalley for an early review copy.

Affiliate link: Support independent bookshops and my writing by ordering it from Bookshop here.

Leave a comment