400 pp. April 22, 2025, Cassava Republic Press. Non-fiction.

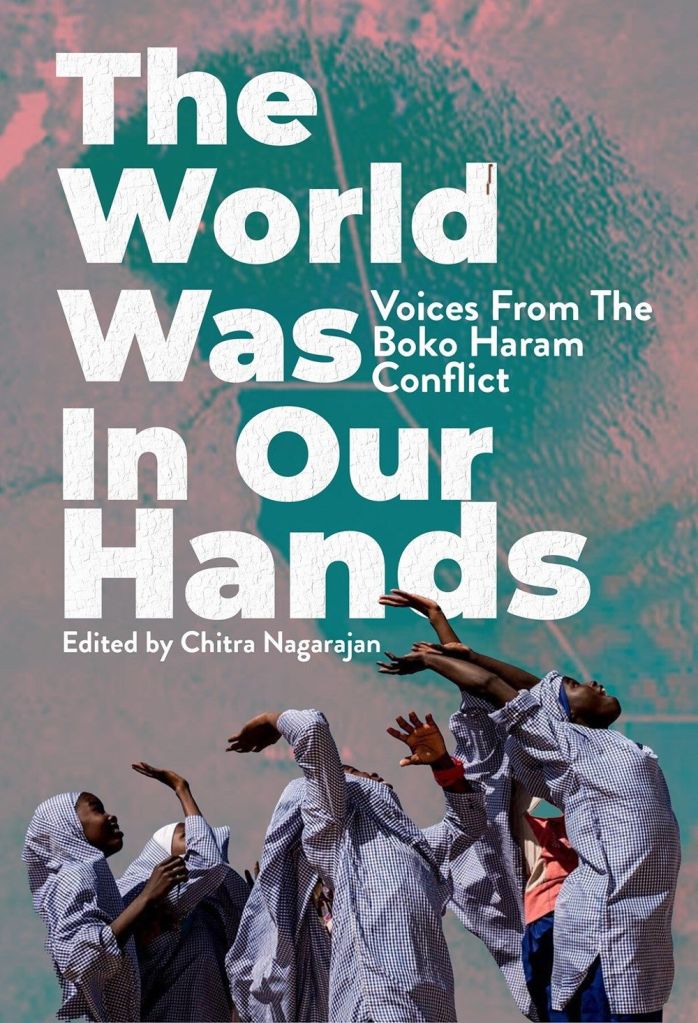

So many stories of suffering in Africa (and most of the Global South) are told by others; so few by the people living them. Here’s a collection of testimonies collected by Chitra Nagarajan over five years, an oral history from people affected by the conflict with Boko Haram: forty-seven interviews in total, with “women, soldiers, farmers, and fishermen,” many displaced; some who were insiders, and many who experienced the violence directly, but others indirectly.

The introduction to the book explains some important facts. The region affected is extensive and includes northern Cameroon, southwest Chad, southeast Niger, and northeast Nigeria. The period covered is 2016-2021. There are many other names used for Boko Haram in the region by the people affected by their activities: kanuriyana, yaran mallam, yanawa, yusufiyya, “those boys”, “those men”, “the fighters.” Nagarajan, the author-researcher, was sensitive in collecting these stories: to language—narrators could relate their stories in their own languages and review what was recorded the same way; to gender—prioritising the stories of women and girls, who are often not heard (falling pregnant, being kidnapped for wives, missing years of school, and experiencing insecurity); to intergenerational relations—the change in dynamics between elders and the youth due to the conflict; and to relations of citizens with the State, often made difficult by the perception that governments are corrupt or uncaring of the plight of their people.

Nagarajan brings great insight in addressing the root causes of the conflict, a complex interplay of religion and an absent State. She records the history of the rise of Boko Haram, from a separatist community founded in 2003 in Yobe State to the increasing popularity of the charismatic Mohammed Yusuf from 2005 onwards. Yusuf was killed by the government in 2009 after attacks by his followers, which led to the creation of Boko Haram:

After Yusuf’s killing, his group went underground, regrouped, and returned, calling itself Jama’atu Ahl al-Sunna li-l-Da‘wa wa-l-Jihad (JASDJ), translated as People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad. The media named it Boko Haram in reference to one of its slogans.

Increasingly violent and more insular under Abubakar Shekau, JASDJ went on a spree of violence which led to retaliation and reprisals from the government—unfortunately, frequently against innocent citizens for not revealing what they knew about members of JASDJ. This is partly what increased the influence of Boko Haram, and led to what has effectively been a civil war.

If you identified them, they would kill you. If you didn’t identify them, soldiers would kill you. What were we supposed to do?

The stories collected here are deeply illuminating about how lives have been disrupted and forever changed by this conflict. People have suffered bereavement, and families are separated. Livelihoods—fishing, farming trading—are ruined, and locals turned into beggars. Many are displaced, and then scorned for being refugees. Children have missed out on years of school. Living in camps means food insecurity: NGOs and the government cannot keep up with food aid, and the land around camps cannot support the huge number of new people. And yet, there are those who are relieved to be in the camps, away from the fighting.

Young women who were taken tell their stories of being Boko Haram “wives”—both those who were taken against their will, and those who genuinely believed in Boko Haram’s message:

We wore a niqab so people did not know who we were, and it felt good to have this power after a lifetime of being told you had none because you were a girl. We wives could do anything we wanted, whatever it was. We would tell other girls and women who had not married them, ‘You bloody wife of a non-believer! If you don’t marry them, you will remain the wife of a non-believer.’ All of us who had taken to the ideology were strengthened. We had completely changed. We felt we were powerful, fearing nobody, but focused on doing the correct actions according to what we were being taught.

There are many stories from those who escaped Sambisa forest where Boko Haram had their base. A mother tells of the grief of having a son who was willingly recruited; she talks about fleeing with her younger sons to protect them from the influence of the older boys, now insurgents.

Some of the stories in the collection are surprising: One woman talks about the many men she saved by hiding them in her home. Another tells how a woman protected her daughter from being kidnapped by Boko Haram (who often kidnap young men for soldiers, and young women for “wives”) by burying her underground.

I spent the whole night thinking and crying. I could not bear for them to abduct Hussaina. What would become of her if they took her? That is how the idea of digging a hole came to mind. I told Hussaina, ‘I cannot let them abduct you. It is better to put you underground,’ and she agreed.

We also hear from the daughter herself about that experience.

There are stories from people in the resistance—because, as always, people resist, and there is resistance to Boko Haram. There are several stories from LGBTQ+ people, at risk anyway in a conservative community, but particularly so under the influence of Boko Haram’s desired return to sharia law. And there’s an arresting interview with a disgruntled Nigerian soldier.

This is what this book does so well: to show very clearly how the causes of the conflict have been manifold, and how every individual involved on the ground has a story to tell. The World Was In Our Hands exists to capture some small part of those stories. Nagarajan’s voice is only in the introduction; the rest of the book is given over to personal testimony.

What can one do in the face of war and death? If you’re in the midst of it, you do your best to survive. If you’re far from it, you try to bear witness. This book has stories of the former, and enables readers to do the latter. It’s been decades of conflict and The World Was In Our Hands is an important and rare record of the Boko Haram conflict from those who were, and are still, there.

I started facing a lot of challenges after a year in this theatre. My war trauma started. I began having problems with everybody around me. I always wanted to be alone, thinking in my head. I barely ate. I hardly slept. I closed my eyes – you would have thought I was sleeping, as my eyes would be closed for more than five hours, but I was not. I was forcing myself to sleep.

Affiliate link: Support independent bookshops and my writing by ordering it from Bookshop here.

Leave a comment