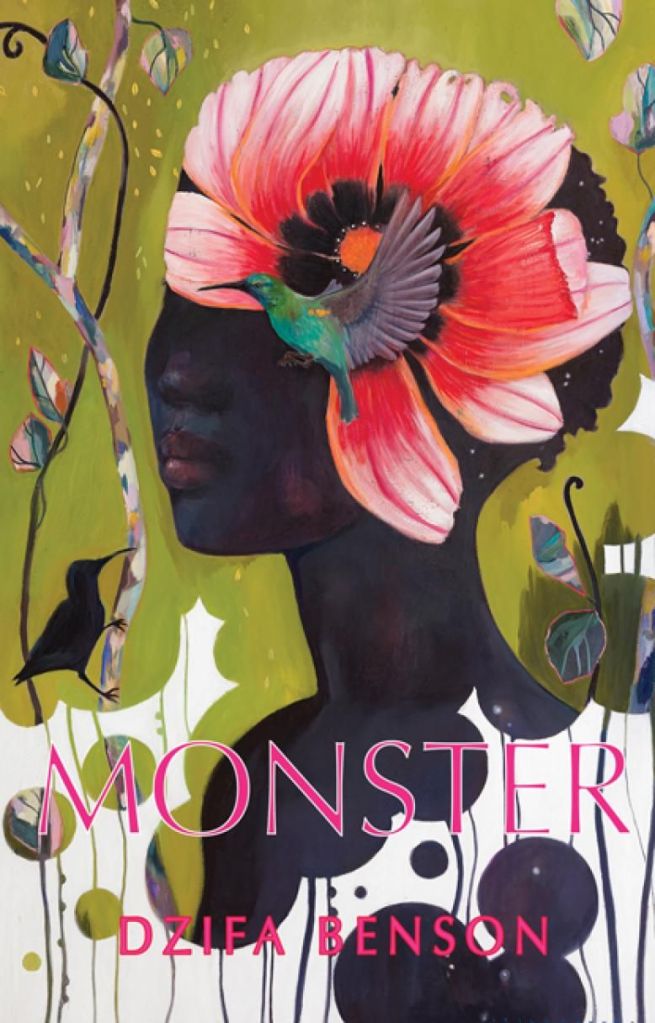

112 pages. Published October 24, 2024 by Bloodaxe Books. Poetry.

Sarah Baartman’s life is the strong, complex centre of this collection of poems, while the stories of other women each take their turn. Ms Baartman—the “Hottentot Venus”—was made an object of curiosity, part of a freak show in 19th century Europe because of her body shape (allegedly). The way she was treated, like an animal in a zoo, is perhaps one of the best arguments demonstrating the barbarity of the “civilising” colonisers.

ladies and gentlemen walk up pray walk up walk up all you who pass this way see and believe for only sixpence the Hottentot Venus just arrived from the far reaches of Empire from along the banks of the River Gamtoos on the border of Kaffraria in the interior of the Cape Colony never before seen in fair England a true phenomenon of nature a most correct and perfect specimen of that race of people the virgin Eve risen from the Garden of Creation to the first primitive level of the Great Chain of Being she has been seen in this metropolis by the principal literati and the curious in general who are all greatly astonished as well as highly gratified with the sight of so wonderful a specimen of the human race and ethnic singularity…

In Monster, we see (we know some details) and imagine Ms Baartman’s life from childhood—she begins life as an ordinary girl in her community, before she’s orphaned—at the Cape, through to White Man’s exhibit in London. Benson restores a degree of agency to her by imagining her interiority as she passes from girlhood to womanhood, tracing her budding sexuality, puberty rites, her relationships and motherhood, before her eventual exhibition in freak shows in Europe. We can imagine hearing her say, eventually,

… I wish to take off this

Hottentot Venus skin. It is heavy.

But this collection is polyphonic; other women—other freaks—suffered similar fates: in Freak Sonnets for Lusus Naturae at bartholomew Fair: Natural-Born, Man-Made and Counterfeit) we learn that Miss Hopwood has wrists where her elbows should be; Miss Pindar has webbed fingers; Miss Crackham has much flab and many folds (she was once the Largest Child in the Kingdom); Miss Van Dyk is very tall; Miss Sidonia is hirsute… And so on. It’s uncomfortable: Benson makes us, the readers, complicit—we, too, are gawkers. The monstrous (them, or us?) women, on the other hand, are feisty, defiant, glorious, majestic.

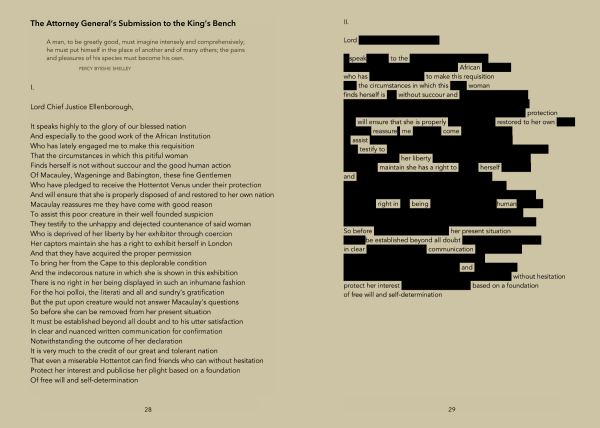

I love the experimentation Benson does with form, like when she takes an attorney general’s submission and makes found poetry from it:

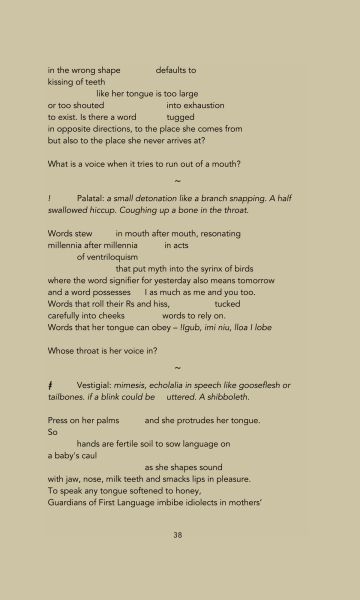

or when she uses Khoe words and diacritics:

Where Ms Baartman ended up—and the indignity of the way she was treated after death—means she’ll always be an object we gawk at—even, unfortunately, when we try to retell or reframe her story. She will always be like a museum object in a display case, presented for our education, titillation, or entertainment.

Monster is a deeply felt experience, a journey into the monstrous feminine (how much more so when that feminine is marked by dark skin). It unsettles, confronts, challenges. If you buy a copy, it will sit on your shelf and haunt you. Reader, that’s a good thing.

Monster is one of my selections for The Continent’s African Books of the Year (pdf download).

Thank you to Dzifa Benson for a review copy.

Affiliate link: Support independent bookshops and my writing by ordering it from Bookshop here.

Leave a comment