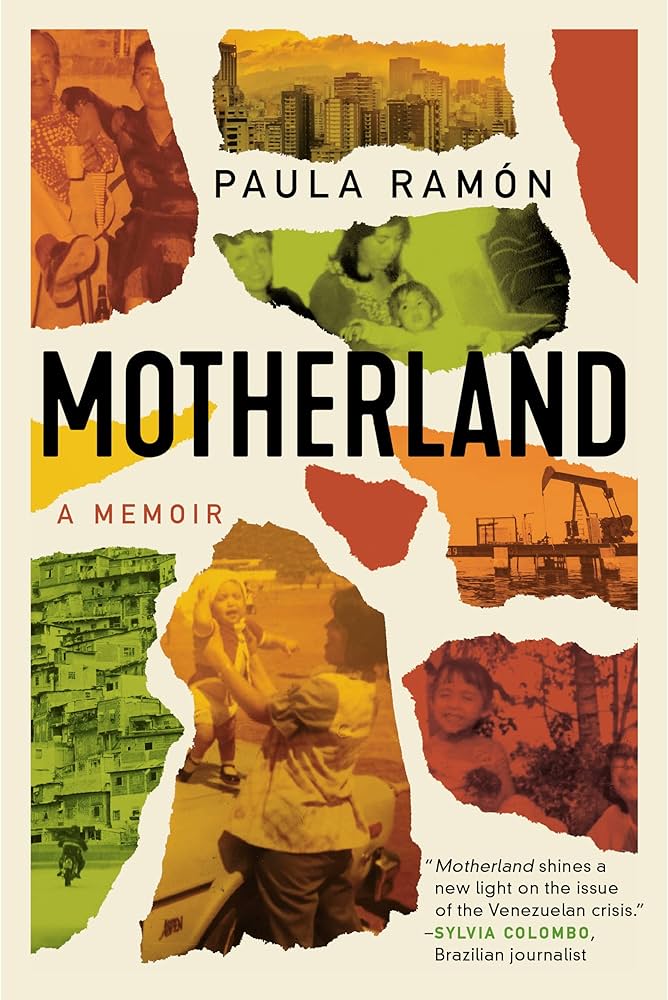

236 pages.

Expected publication date: Oct 31, 2023 (Amazon Crossing)

Non-fiction/memoir.

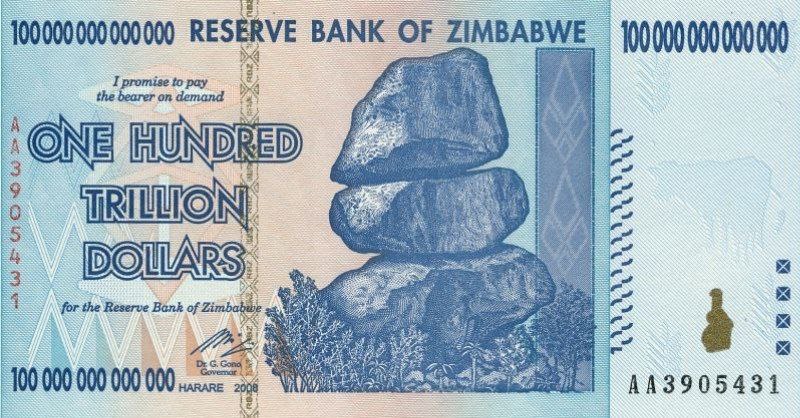

People often joke about Zimbabwe’s $100,000,000,000,000 (it’s like spelling Mississippi) note, or make clever comments about the parallels between Venezuela and Zimbabwe—but these jokers and commenters do that rather at the expense of real people, of real lives ruined by economic catastrophe. It’s like being caught up in a war, but without the world’s empathy. Instead, citizens are shamed, scorned, mocked—somehow taking the blame for authoritarian leaders’ failed policies. I know, because I lived it, and still do.

I feel that shame in Ramón’s account—and who better to understand what Venezuelans went through (apart from other Venezuelans) than a Zimbabwean? Because the parallels between our experiences are frightening. I realised, towards the end of the book, how much of my own trauma I was reliving. Like Ramón, I was lucky: I had a university education, and I managed to leave—so I was able to help support my family from outside the country. Although I came back home just before the worst of it (2007-8), my savings may have saved our lives. I experienced or watched happen to the people around me all of the terrible things that Ramón relates: lost savings, pensions, property; a broken healthcare system leading to deaths and disability. Starvation, empty supermarkets. The black market for everything: food, even cash. How incredibly far a tiny amount of forex could go, and people working a whole month to earn enough to buy a loaf of bread. Queues for basic foodstuffs—sugar, maize meal—with no guarantees. (Milk and margarine were a fantasy; we once baked scones without.) Shopping across the border if you wanted to get anything. I even travelled in the back of a private truck between cities, and also over a border, because public transport was a dream—no fuel anywhere. Absolute desperation. And the toll on one’s mental health? Incalculable.

So, this book hit me on so many painful levels. Ramón‘s experience is my own, and personal. It’s that of so many Zimbabweans, and, from her account, many Venezuelans. Her brothers’ experiences as less well-educated migrant workers are the experiences of my cousins, and so many fellow Zimbabweans. In that, I am an unusual reader; perhaps this memoir may have less appeal to people who haven’t lived through this. But we can always all bear witness, stand in solidarity, and learn something when fellow humans suffer. And if it’s not you or yours today, tomorrow it may well be: nothing on this troubled planet is ever perfectly secure.

Thank you to Amazon Crossing and to NetGalley for access.

Support independent bookshops and my writing by ordering it from Bookshop here.

Leave a comment